DESIGNING FOR THE FINAL FRONTIER

DEATH x TECHNOLOGY DIGITAL x PHYSICAL GAME DESIGN

INTRODUCTION

The future of legacy.

Death remains one of the most meaningful and most avoided topics in American culture. While people express strong preferences for legacy, remembrance, and digital identity, they rarely communicate these wishes to the people who matter most.

A challenged ourselves to transform an emotionally charged and culturally silenced problem into an accessible sparked conversation that strengthens and empowers people to make informed choices about their life and their afterlife.

CATEGORY

Death Industry

Physical & Digital Game Design

ROLE

Digital Identity & Data Ethics

Gaming Mechanism Strategy

Thematic Analysis

Diary Studies

CHALLENGE

How might we reimagine the experience of death, transforming it from a feared, avoided subject into an empowering conversation that helps people connect and intentionally design the continuity of a life story?

RESEARCH AT SCALE

A layered research approach built for clarity and scale.

-

Expert insight shaped the foundation of this work. Memorial designers, digital identity researchers, mortuary professionals, grief counselors, and end of life advocates provided a clear view of the systems, emotions, and cultural blind spots that define how people plan for death.

-

Open questions and hypothetical end of life scenarios revealed instinctive reactions and decision patterns. The format surfaced what people understand, what they avoid, and where meaningful intervention is possible.

-

Participants were asked to imagine they would die soon without a defined timeline. The ambiguity created honest choices and exposed the values, fears, and priorities that typically remain unspoken.

-

Longitudinal reflection captured how thoughts about death, legacy, and digital identity shift over time. The method revealed quieter behaviors such as avoidance, procrastination, and moments of clarity.

-

A deep scan of digital platforms and account management policies clarified how major companies handle data, identity, and access after a person dies.

-

A scan of leading digital platforms revealed how current products address death, legacy, and account transition. The review highlighted fragmented tools, unclear pathways, and a lack of user centered features for planning digital continuity. This work mapped the landscape and identified where meaningful differentiation is possible.

MITZI WEILAND

Grief Counselor/ Death Cafe Facilitator at

The Wallingford Community Center

Seattle, WA

“How we want to die is the most important and most avoided conversation in America. Death Over Dinner flips that silence into dialogue, connection, and agency.”

Call it the post mortem paradox: the one person who can act cares least, and the people who care most can’t do anything.

GREG LUNGREN

Memorial Designer/Artist

Order of the Good Death Founder

Seattle, WA

“Death Cafes offer space to talk about death. These candid gatherings break silence & normalize mortality.”

WILL ODOM

Design Researcher, Professor School of Interactive Arts + Technology at the Simon Fraser University

ELIZABETH GRAVOUGEL

People’s Memorial Association

Interaction Designer

Seattle, WA

NORA MENKIN

People’s Memorial Association (PMA)

Executive Director

Seattle, WA

EXPERT INTERVIEWS

Death, Honestly

Talking about death isn’t easy. We turned to the experts who face it every day. Their guidance shaped our approach, helping us create conversations that are grounded, balancing emotional depth with practical clarity.

"We talk about data privacy like it's urgent, but after death? It's a forgotten frontier, unregulated, unclaimed, rewriting our stories without our permission."

JEB BRUBAKER

Design Researcher, Professor at College of Media University of Colorado Boulder

Boulder, CO

Rather than asking abstract questions about “legacy” or “planning,”

we placed participants inside a near-future death scenario with no timeline, no constraints, no scripts.

This method worked because mortality collapses indecision. People stop intellectualizing and start revealing their real values, real regrets, and real beliefs about what should happen after they’re gone.

In 20 minutes, we surfaced insights traditional interviews miss entirely:

emotional readiness, digital blind spots, planning behavior, and the unspoken impact on loved ones.

THIS WAS A PERMISSION TO TALK ABOUT DEATH & IT WAS KINDA FUN.

The innovation wasn’t in the scenario.

A hypothetical death is the fastest route to the truth.

A FRAGMENTED ECOSYSTEM

Rest in Policy: Landscape Analysis

The digital-death ecosystem is not designed for grief or clarity.

Platforms treat digital remains as property, not identity, and policies prioritize corporate risk. Families are left to navigate confusing processes at the exact moment they’re least able to manage them.

Across platforms, death policies share no common language, workflow, or user journey. Each company operates in isolation, creating a patchwork of inconsistency and emotional friction. Loved ones must relearn every process, reliving their loss with each platform.

Key Failure Modes

Divergent terminology

Memorialize, deactivate, close, remove, legacy contact, trusted contact, inactive manager, verified representative — none of these terms align across platforms.

Variable documentation requirements

Some platforms accept a death certificate; others require legal proof of authority, notarized statements, or government ID.

Asynchronous support systems

Most platforms lack human support, relying instead on generic help centers or automated forms.

Redundant emotional labor

Loved ones must repeat steps across every platform, often reliving the loss each time.

Platform-by-Platform Breakdown

LinkedIn account closure only; requires immediate family + documentation

Facebook memorialization system + legacy contact; complex permissions

Instagram memorialization but no account management by survivors

Google pre-planning option (Inactive Account Manager) + post-death legal process

Twitter deactivation only; username eventually released

Pinterest removal or deactivation with verification

DEEP HUMAN TRUTHS

Participant Insights

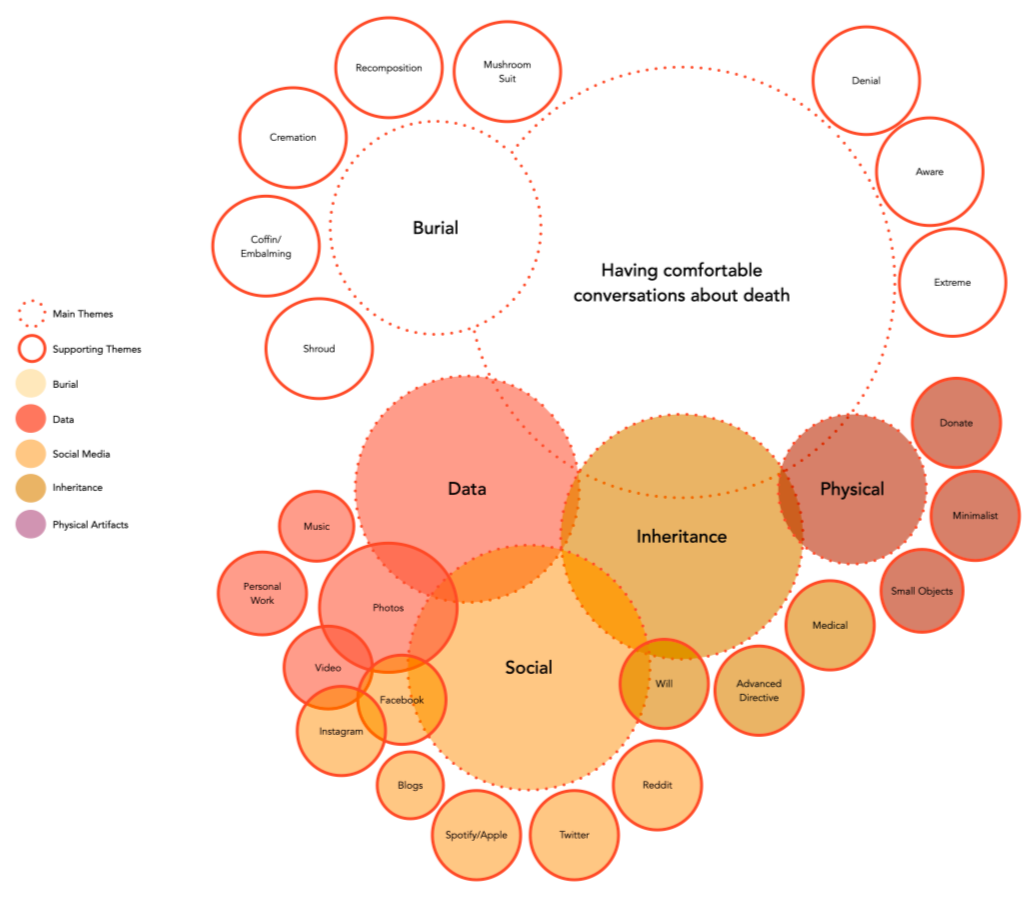

The following insights synthesize data across all methods: expert interviews, semi-structured interviews, hypothetical mortality scenarios, diary studies, and lightweight prototyping exercises.

Deep human truths surfaced across interviews, scenarios, diary studies & expert conversations. Each insight reflects a crosscutting emotional pattern, not just an isolated quote or behavior.

-

Most individuals carry detailed mental models of what they want to happen after they die, but they rarely communicate these wishes to the people who will ultimately be responsible for honoring them.

Across interviews and scenarios, participants revealed a striking paradox:

They have clear internal ideas about their end-of-life wishes

They assume loved ones “already know”

They avoid initiating conversations because of discomfort or cultural taboo

This silence creates avoidable turmoil. People expect their values to “be understood,” but never articulate them.

This is the emotional bottleneck:

People are ready to talk about death in theory, but unprepared to talk about it with the people who matter.

Result:

Loved ones are forced into emotional decision-making at the worst possible time, navigating ambiguity instead of honoring clarity.Representative Quotes

P4: “My grandma had everything organized… it made everything less stressful.”

P4: “We share grief together, but never the deeper conversations about what it all means.”

P3: “Talking to my parents means they have to admit they’re going to die. That's the hardest part.” -

End-of-life planning is not self-oriented; it is relational. People want to remove logistical, financial, and emotional burden from the people they love.

Participants rarely framed planning as “my death plan.”

They framed it as:“How do I make this easier on them?”

“How do I spare them confusion?”

“How do I leave them in a good place?”

This protective instinct often becomes the only motivator strong enough to overcome avoidance.

But:

Most people don’t know what “planning” includes — funeral logistics, disposition choices, digital accounts, financial playbooks — so intentions rarely translate into action.Representative Quotes

P7: “This is the playbook of how to get by if I’m gone. I just don’t want her to struggle.”

P2: “I’d immediately think about the costs — I know what a strain it puts on the people left behind.”

E4: “Talking early allows families to understand the meaning behind the legacy.” -

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more.Participants defined their digital presence as “personal archives,” but experts and bereaved individuals defined it as a shared emotional ecosystem.

This mismatch is profound.

Most people believe:

Their accounts are “just for them”

Their data has meaning only during their lifetime

Deletion or neglect affects no one else

But loved ones see:

Photos as anchors of memory

Posts as shared history

Feeds as a form of presence

Social profiles as living memorials

This relational layer of digital identity is invisible to users but unavoidable for survivors.

Representative Quotes

P1: “They’ve served their purpose for me — if they go away, that’s fine.”

E5: “The post-mortem paradox: the person who can act doesn’t care, and the people who care can’t act.” -

Participants articulated three broad preferences for their digital remains—delete everything, leave everything, or have someone steward their accounts—but none understood how these choices affect their grieving connections.

Key tensions emerged:

Notifications can retraumatize

Data loss can worsen grief

Lack of access causes logistical nightmares

Leaving everything “as is” can create emotional stagnation

Participants thought about control, but not about impact.

This gap produces emotional distress for survivors who must navigate:

Locked accounts

Platform support systems that break under stress

Unplanned digital traces that feel either overwhelming or insufficient

Representative Quotes

E2: “A Facebook profile can keep hurting people through notifications they can’t control.”

P3: “We were grieving and trying to fight with platform support at the same time.” -

Participants overwhelmingly wanted to pass down a curated set of memories—not their entire digital footprint—because only a small portion of their data holds emotional weight.

Across interviews:

Photos emerged as the primary form of meaningful digital memory

People wanted their “best stories,” not their “entire archive”

They lacked tools to curate meaning from volume

They wanted tangible formats (prints, books) despite living digitally

The real legacy isn’t data — it’s discernment.

Representative Quotes

P10: “Photos are the most meaningful thing. That’s how people remember your face.”

P8: “My blog, my photos… they’re personal. That’s what I’d want preserved.”

P12: “30–100 photos — the ones that matter. But they’re scattered everywhere.” -

Participants expressed awareness (“I should back up my phone”), but lacked understanding of settings, tools, or why any of it matters for legacy.

This creates a high-stakes dependency:

No backups means no memories

No password sharing means no access

No designated contacts means no continuity

People mentally link backup to device failure, not death.

Their systems are built for convenience, not continuity.Representative Quotes

P5: “I have a backup, but no one has access if I die.”

P2: “I only think about backup when my phone nags me.” -

Across participants, there was a deep desire for valued possessions—both physical and digital—to continue bringing joy to someone else. But without a trigger event or system, this desire remains aspirational.

Reasons for inaction include:

Youth (“I’ll do it later”)

Good health (“I’m not old enough to think about this”)

No obvious recipient

No structured prompt

No emotional urgency

This creates the “Sentimental Bottleneck”:

People know what matters to them, but lack a framework that turns intention into transfer.Representative Quotes

P1: “I want my film equipment to go to someone who actually enjoys it… I just haven’t planned anything.”

P7: “My fishing gear… that’s my religion. I want someone to get that same peace.”

P4: “I’d donate my guitars… I just haven’t figured out where.”